THE DEVIL'S BACKBONE & BAKE OVEN

GRAND TOWER, ILLINOIS

GRAND TOWER, ILLINOIS

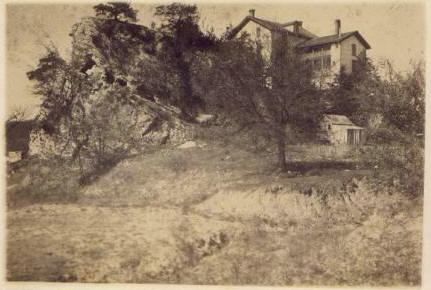

The foundry house as it looked many years ago.

The Ruins of the foundry house on the side of the Devils' Bake Oven

Tower Rock

The small town of Grand Tower slumbers peacefully along the muddy banks of the Mississippi River. Once a booming ironworks town, there is little remaining of the city that was in these modern times. Regardless, Grand Tower has been a southern Illinois landmark for years, thanks to the vast array of tales that have been told about the area, including one of the most famous ghost stories in the region.

When Jolliet and Marquette journeyed down the Mississippi River in 1673, they recorded in their journals a large rock that is known as Tower Rock today. At one time, it was also known as Le Cap de Croix, meaning "the Rock of the Cross" to the French settlers and explorers. The name was given to the landmark after three French missionaries erected a large wooden cross on the rock’s crest in 1678.

When Jolliet and Marquette journeyed down the Mississippi River in 1673, they recorded in their journals a large rock that is known as Tower Rock today. At one time, it was also known as Le Cap de Croix, meaning "the Rock of the Cross" to the French settlers and explorers. The name was given to the landmark after three French missionaries erected a large wooden cross on the rock’s crest in 1678.

During the heyday of river travel and exploration, a number of people were killed in the rapids that sometimes run at the base of the rock. Thanks to this, the Native Americans were convinced that evil spirits lurked here, waiting to claim the lives of unwitting victims. The white men who settled the area would later acknowledge these beliefs by giving the towering rocks a suitable name. There is one landmark called the Devil’s Backbone, which is a rocky ridge about one-half mile long. It begins on the northern edge of Grand Tower’s city limits. If you look closely, you can see that a large piece of the knobby “spine” is missing. A railway spur once passed through here and connected to the ironworks. At the north edge of the Backbone, there is steep gap and then the Devil’s Bake Oven, a larger rock that stands on the edge of the river and rises to heights of nearly one hundred feet.

When river navigation came to the Mississippi, keelboats and flatboats passed the area in great numbers. According to early records, the rapids along the Backbone caused many problems for pilots when the river was in its low stages. Crews often had to disembark and walk along the shore, using ropes to pull their boats through the rapids. When going downstream, it was often necessary to reverse the process and use the long ropes to ease the boats carefully along.

During the steamboat days, the Backbone served as a landmark for river pilots. It also afforded an excellent lookout point from which boats could be seen coming for miles away. The two outcroppings of rocks also made excellent hiding places for Indians and river pirates to hide and wait for their victims to come along. In fact, the raids by river pirates became so bad that in 1803, a detachment of US Cavalrymen were dispatched to drive the outlaws from the area. They set up camp at the Devil’s Bake Oven from May to September of that year. While the soldiers waited, the river pirates simply moved their camp to a rock overhang on the Big Muddy River. The place is still known as “Sinner’s Harbor” today. Once the military left, they returned to attacking boats on the river. Later on, as settlers and a semblance of civilization arrived, the pirates moved on and the rapids beneath the Devil’s Backbone became a much safer place.

When river navigation came to the Mississippi, keelboats and flatboats passed the area in great numbers. According to early records, the rapids along the Backbone caused many problems for pilots when the river was in its low stages. Crews often had to disembark and walk along the shore, using ropes to pull their boats through the rapids. When going downstream, it was often necessary to reverse the process and use the long ropes to ease the boats carefully along.

During the steamboat days, the Backbone served as a landmark for river pilots. It also afforded an excellent lookout point from which boats could be seen coming for miles away. The two outcroppings of rocks also made excellent hiding places for Indians and river pirates to hide and wait for their victims to come along. In fact, the raids by river pirates became so bad that in 1803, a detachment of US Cavalrymen were dispatched to drive the outlaws from the area. They set up camp at the Devil’s Bake Oven from May to September of that year. While the soldiers waited, the river pirates simply moved their camp to a rock overhang on the Big Muddy River. The place is still known as “Sinner’s Harbor” today. Once the military left, they returned to attacking boats on the river. Later on, as settlers and a semblance of civilization arrived, the pirates moved on and the rapids beneath the Devil’s Backbone became a much safer place.

The years passed and the town of Grand Tower began to grow. It was first known as “Jenkin’s Landing”, but the name was later changed to correspond with the recognizable river landmark. The town became a busy river port where goods were shipped and received daily. On the west side of the Devil’s Backbone, between the rock formation and the river, is the site of two vanished iron furnaces that operated there until around 1870. Iron ore was brought to these furnaces from Missouri and they were fired with coal from Murphysboro. It is said that Andrew Carnegie once considered making Grand Tower the "Pittsburgh of the West".

The population soon expanded and a lime kiln was started in Grand Tower, along with a box factory and a shipyard. A number of river barges and one steamer, the “Mab”, were constructed here. New businesses came to the area and even an amusement park was opened on Walker’s Hill, just east of town. Time marched on however and the population dwindled. A cholera epidemic many years ago wiped out a number of the residents and the decline of river transportation succeeded in driving away the rest. Grand Tower was once a town of more than 4000 souls, but only a fraction of those still remain. One local even said to me that the graveyards hold more bodies than the town can boast as residents these days.

It was the expansion of the iron industry in Grand Tower that brought about the ghost story that still haunts the town today. The Devil’s Bake Oven also played a major part in the story because besides serving as a river landmark for years, it became the site of Grand Tower’s first iron works. When the new industry came, several attractive homes were built for the officials of the company, including the house built for the superintendent. This house was built on top of the Devil’s Bake Oven. The foundation of the old house can still be seen on the eastern side of the hill today and it is here where the ghost is said to walk. It has been said that she is heard among the ruins of the old house, where tragedy and despair in the past have led to a modern-day haunting.

According to the old story, the ghost is that of the superintendent’s young daughter. The girl was said to be very beautiful but was also sheltered and naive about life. Her doting father kept her away from the rough men of the foundry and although she had a number of suitors seeking her hand in marriage, he accepted none of them. Finally, one day, the girl fell in love with one of the young men who came to court her. As is often the case, the young man was a handsome, roguish and irresponsible fellow of whom her father strongly disapproved. He forbid her to see him and after she slipped away to meet the young man a few times in the night, he father confined her to the house for a long period of time.

The young man was convinced to move on from Grand Tower, possibly from money offered by the superintendent, and the young girl wept over him for days and weeks. At last, either because of grief or because of some illness brought on by her despair, the young woman died. Her father felt so guilty about the incident that he comitted suicide.

But she did not leave the Devil’s Bake Oven.

The spirit of the young girl was said to have lingered at the site of the house. For many years after her death, visitors to the area reported seeing a strange, mist-like shape, which resembled the dead girl, walking along the pathway and vanishing among the rocks near the old house. Her disappearance was often followed by the sounds of moans and wails. It was also believed that when thunderstorms swept across the region, those moans and wails would become blood-curdling screams.

How long the girl haunted the place, and whether she still does or not, is unknown. It was said that the ghost appeared long after her father’s house was razed and the timbers used to build a railway station. But does the ghost still haunt the Devil’s Bake Oven today? If she does, she probably finds the area unfamiliar to her now. The stone landmarks still remain but the land around it is greatly changed. The town of Grand Tower has also faded into a scattering of houses and there is little to remind us of the history that once enriched this small area.

And little to remind us of the young girl who once died here of a broken heart and whose spirit refuses to rest in peace.

Grand Tower, Illinois is located on Highway 3 in southern Illinois. The Devil's Backbone is a large rock point that leans out toward the river, just a short distance form Grand Tower. The Devil's Bake Oven, a large rock hill, is just south of the Devil's Backbone. A natural gas pipe bridge on the Illinois side marks the area. The ruins of the foundry house can be found a short distance down a dirt road, at the bottom of the Devil's Bake Oven hill.

Source: http://www.prairieghosts.com